Steve and I have decided to try and publish the results of this study. I’ve made a mindmap that will allow us to coordinate the planning of the paper and upcoming experiments to include in the paper. This page will be updated frequently so check here often.

Yearly Archives: 2011

Analytics Monday: Week of 12/5/11

The big news of this week is the addition of FigShare to my open notebook repertoire. I uploaded the Crumley data there for all to access. While technically the data was already open and accessible through this notebook, having it in more than one location is better!

I think I’m losing the goal of analytics. While I love looking at the hits and it is a very short term reward, I think the important information is not how many people are visiting the site, but where the people are coming from. By knowing where the audience is visiting from, you can better gauge the level of impact you may have on the scientific community. As an example, a lot of my traffic comes from Google searches – I still get a ton of hits for “Open PCR” (and will probably get more because of that mention there) – which is great, but probably not measurable right now in terms of traditional impact. But every now and again I get a visitor who is referred from a site that links my blog. While right now this is kinda small potatoes, eventually (hopefully) someone will link a protocol or a data set, which to me is just as good as a paper citation. That to me says “this person has a pretty good written protocol that you can trustfully follow” or “here is some interesting data based on a similar set of experiments.”

When that happens (and it will) and it happens to others (and it will as well) then ONS will become a viable outlet for more than just a handful of scientists. So today let’s look at some referrers:

- A good number of visitors came from search results and referrals. The referrals are listed as: Facebook (predominantly), Google Plus, LinkedIn, Andy’s Notebook, and Wikipedia. I’ve noticed that I’ve been getting some hits from the ONS Wikipedia page which warms my heart.

- As you can see, I’ve been hitting the social media outlets pretty hard. I actually don’t use twitter that frequently, but I have my posts auto-populate twitter and they go viral from there. I’m pretty amazed because I’ve always said Twitter is useless. It works pretty well for about a few hours and then goes dead, that’s how fast information is nowadays. As for the rest of the social media, I only use it because how are other scientists supposed to come across things that may interest them if I don’t do some form of promotion?

- A surprise to me is that most of my hits are getting tracked as “campaign” and I don’t know what that means! I know one component of campaigns has to do with visitors from RSS feeds and another source of campaign traffic are hits from Twitter. I would have assumed twitter would go under referrals, since other social media is sourced as that. I’ll have to investigate further since I don’t understand the associations, but it is interesting that I could even have a campaign association for an open notebook.

UPDATE: I removed the section that links to the FigShare Crumley data. I thought the embed box on FigShare linked to the data, but it instead linked to the site itself. Oh well.

Today I learned how to synchronize yeast cells

I spoke with Kelly Trujillo about cell synchronizing after Koch had mentioned to me that we may need this for ddw yeast studies. He mentioned that he was going to be synchronizing for a study that he was setting up and that I could come learn the process. So I took him up on his offer.

I have to say, the protocol is surprisingly simple. Kelly grew a colony, diluted it to about 0.1 OD and then let it divide up to 0.4 OD. We looked at the asynchronous growth and then he added some mating pheromone (details to come) to some of the culture to halt the cells in G1 phase of cell division. From here, he could synchronize them to enter S phase by using hydroxyurea (HU) after washing out the mating pheromone. The remaining culture was arrested in G2/M phase with the drug Nocodazole.

We paused during each step to look at each culture (asynch, G1, S, and G2) but I have no pictures. I do have the knowledge to do it myself and hope to incorporate this in the DDW experiments shortly. A preplanning thread will come soon.

DDW4: Day 7 cropped photos of tobacco seeds

And here are the cropped pictures of the tobacco seeds (no past photos). Also courtesy of JPEGcrops.

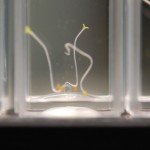

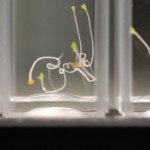

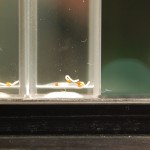

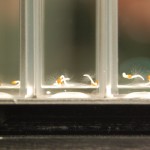

DDW4: Day 7 cropped photos of Arabidopsis (and some pics from DDW3)

Here are the cropped photos. I used a program called JPEGcrops to mass crop the images from day 7. It was sweet and quick. I also included (uncropped) photos of the DI and tap water samples from Trial 3 of the DDW experiment. I don’t know if the curviness is real or not so I’ll let you comment below if you think it’s real. My money is on yes!

I updated the FigShare figures and slightly modified the excel files. Check it out.

Repeating Crumley Experimental Data on FigShare!

It took me a while, but I finally got my data from the Repeating Crumley set of experiments up on FigShare. Of course, I didn’t call it Repeating Crumley there since that experiment has no context. You can download the data sets and figures here:

Repeating Crumley FigShare Data and Figures

The interesting thing about this site is that your data remains your data but is openly accesible. Each upload is given a citation. Mine is:

Salvagno, Anthony; Koch, Steven J; Salvagno, Anthony (2012): Repeating Crumley: Tobacco Seed Growth in D2O. figshare.

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.89655

Retrieved 22:15, Mar 02, 2015 (GMT)

Also there is a little section for social media promotion and it tracks the page analytics for you as well. That is pretty neat!

It did take me a while to get this up on FigShare unfortunately. For a while I couldn’t log in with Twitter, Facebook, or Google. I was asked repeatedly to sign in while trying to upload stuff. Eventually I just gave up and created a new account. Then when I tried to upload my first images, the site was unresponsive. I did spend a considerable amount of time organizing my resources so it would be presentable on FigShare, so that added to the mess a bit. And I also spent some time collecting links from my notebook to incorporate with the data so all experimental information can be collected. I also monified my active experiments page a little so some of the links are easier to navigate.

Despite how time consuming this first run was, it was definitely worth it.

DDW4: Day 7

Focus on the middle sample in each image.

I have to say I’m convinced. I’m convinced that the root hairs are a real phenomenon of growing in ddw. All of the tobacco seed samples (havanna and virginia gold) growing in ddw have at least one or two seeds that have root hairs. ALL. The DI and the tap water samples are barely growing hairs. There is a clear difference between these hairs and the DDW samples.

As for the arabidopsis. I don’t know. The only thing I’m noticing is that the stems are growing very crooked. So crooked that most of the seedlings have intertwined. This is tough to confirm because the DI sample barely sprouted, but the tap water sample appears to have longer persistance lengths (to borrow a word from DNA). By this I mean the angle of curvature is greater in the tap water than in all the ddw samples which tend to curve like no ones business.

I can confirm this by comparing to the previous batch of samples. The tap and di water samples had similarly longer curve radii, while the ddw (which had to start after) seeds got all tangled together.

What should I make of this?!?!?!?!?

Introducing Shotgun DNA Mapping

Before I got immersed in the world of deuterium-less water, I was a rabid DNA-man. The project was Shotgun DNA Mapping which was a term we invented to describe a quick protocol for mapping a DNA sequence.

In theory, the technique was awesome: unzip a DNA sequence with optical tweezers and compare the data to a library of simulated data for a given genome to figure out where you are in the genome. This would lead to a bigger project called Shotgun Chromatin Mapping which was the similar except you could map protein locations on DNA fragments using the same technique.

For this to work, you need three components:

- Optical Tweezers – to unzip DNA and record data

- DNA – to unzip

- A computer simulation – to simulate DNA unzipping and match recorded data to simulated data

I dedicated a few blog posts in my other blog to discussing the basic principles of the project in case you need to get caught up to speed. But in case you don’t have time for all that, here is the whirlwind summary:

Optical tweezers are an optical system that requires a laser, a microscope objective, a condensor, some steering components, and a detector (in our case a quadrant photo diode) among other things. The laser is focused by the objective and this focus can exert forces on tiny dielectric particles. Our particles are microspheres. (The blog posts linked explain the physics of this in great detail.)

Using some principles of biochemistry I can attach a microsphere to a DNA fragment that is specially designed to: (1) tether to a glass slide using antibody-antigen interactions, (2) contain a weak point in the DNA backbone to begin unzipping, and (3) be versatile enough to use a variety of different DNA sequences.

I can then tether the DNA to slides and place them in the path of the laser. The focus will attract the beads, and if the tethering process works properly then the beads will be attached to DNA. This is how we are able to exert forces on the DNA. Our detector is used to track the laser movement, and those signals get converted into force data. The forces recorded are on the order of pN, which is insanely small but enough to distinguish from background noise.

Once we have unzipping data we can use a computer program to compare this information to a library of simulated unzipping data for a genome. In our proof of principle study we used the yeast genome, so we simulated unzipping fragments for the entire genome and then used actual yeast genomic DNA to unzip.

Unfortunately I hit an impassable road block in the experiment. The DNA I created wouldn’t unzip. I tried everything I could think of, reworked the entire process and tried to come up with alternate methods for creating the DNA fragments. Ultimately I had to switch to the project I’m working on now…

…But that doesn’t mean that the project was a complete failure. I’m sure the protocols and techniques I employed can be useful to someone, somewhere, someday and so I’m going to highlight posts from my old notebook here as a way to kind of direct attention to the protocols that summarize my project well and were most useful for me.

In this way, one wouldn’t need to sift through mounds of information just to find one thing. And it would provide visitors here a little more information about my background and something I keep alluding to. All in the name of open science!

A history of my open notebook aka Why I chose WordPress for my notebook…

I began my open notebook 3 years ago on OpenWetWare.org (OWW). Before that the lab was using a private wiki provided by OWW for about a year and a half, so choosing the wiki for my public notebook was natural.

The wiki was perfect (at the time) for what I needed. I had a place to keep reliable notes, I could learn HTML, CSS, etc easily, and I could mold my notes however I saw fit. The wiki was a blank canvas and I was the artist (at the time I was not angling to be a designer but the analogy works well).

As my notebook expanded I began to grow frustrated with the wiki’s style. In order to insert a table I had to code the HTML or CSS for it every time, and I used tables frequently. Whenever I had to make a new page (every day) I had to record the page’s url so I could keep track of what was on each page. As I added content, I had to categorize pages so that I could provide some semblance of navigation. If I misspelled a category or even used a different case (capital vs lower case) that would create a new category which would fracture my content.

I found myself frequently searching for my own content and turning up nothing even though I KNEW I had written something. It became tiresome.

Luckily, OWW expanded capabilities and cloud technology was developing. I used Google Docs for tables and would just embed them in my notes so I didn’t have to write new HTML code every day. OWW developed a notebooking platform that would create new pages chronologically as you needed. And I learned about dynamic page listing which could track almost anything on the wiki in whatever fashion I needed. I could make a page, and tag it with a category, and DPL would only list whatever I specified. Thanks to Bill Flanagan (who was (still is?) the Senior Tech Developer of OWW back in 2010), I was able to get the features I desperately needed in OWW.

Eventually I soured on OWW. It became difficult to keep my notebook organized. DPL couldn’t keep track of everything and going back chronologically took way too long. What’s more is that in order to keep my notebook pristine both organizationally and navigationally I had to create templates that would do most of the work for me, but even then I was still doing a lot manually. Every day.

The reason is because a wiki inherently has no organizational structure. Look at Wikipedia. It’s a great resource, but you can’t just go to the main page and browse articles. Lucky for the world, that the first hit for a search term on almost any subject takes us there otherwise no one would ever use it!

At this point (around May 2011) I was already relying on Google Docs for a lot, and other cloud software (Friendfeed, Youtube, Evernote, BenchFly, etc) for everything OWW and Google Docs couldn’t do. I decided to go all cloud and organize it all via Google Docs.

At the time the idea made sense. Docs are easily searchable, and organizable. You can create folders (categories) or even add some buzz words to each doc that would act like tags when you search. The design was very much like email, so it is very intuitive. I could also make pages public to keep my notebook open.

Then I discovered something interesting.

The public pages weren’t indexed by Google, the very company that hosts the software. That means that when I used Google to search for notebook pages that I had created, I would get no results.

I attempted to fix this by tweeting my newly created pages. I had read in several places that linking to a non-indexed page from an indexed page would make the first page indexed. And I knew Twitter was indexed in some capacity because you can get search results from there. Unfortunately this did not fix the problem.

So I set out for a new solution. I needed a platform that was search engine optimized (for searching reasons), had organization built in, and could integrate with other cloud technologies.

That brought me to WordPress.

The transition was really easy because I’ve been blogging with Blogger for slightly longer than I’ve been open notebooking. And I knew it had all the features I needed (list time!):

- Blogs self organize reverse chronologically, so the most up-to-date content appears first. You can enhance the organization with tags and in WordPress you can go deeper by using nested categories.

- WordPress allows customization to the extreme. You can install plugins that allow you to integrate Google Docs, photo slideshows, youtube videos (or BenchFly 😉 ), etc. You can add change the appearance of WordPress as well. You can install themes that allow you to control what content users get. Have a photo blog? There’s a theme for that! (I’m using the basic 2011 theme.)

- Navigation is rather easy as well. You can go back through time at the bottom of every page and you can view posts by month, tag, or category. You can do even more if you cleverly use the static page feature. I’ve used it to link specifically important posts through my “Active Experiments” page. This ensures that pages that I want to never lose track of stay available without sifting through months of posts.

For now, WordPress seems like the best available platform and since it is constantly being developed it should remain that way for a while. The fact that there is a cloud hosted version (I’m self-hosting) provides a better chance for survival. Competing content management systems (CMS) like Drupal and Joomla rely on self hosting, which works for some, but not everyone.

One of the biggest issues for or against open notebooks are ease of use. Everyone wants to use a system that requires little maintenance and ensures efficiency. After all, no one wants to have to work on their notebook after working really hard to get data and write results and conclusions.

I think right now WordPress is that system. I’m sure over time that will change, but for now, this is the best and probably the easiest to sell for anyone on the fence about going open notebook.